The secretary problem demonstrates a scenario involving optimal stopping theory, the problem of choosing a time to take a particular action for the desired outcome.

It is also known as the marriage problem, the googol game, and others.

The problem describes a scenario of hiring a secretary. The rules are:

- You will have a known number of applicants for the job.

- Each candidate has a rank as to how qualified they are.

- After each interview, you must make a decision to hire or not hire. You cannot choose an applicant after interviewing other applicants.

The goal is to get the best possible candidate as often as possible.

*Note - If you do not know the number of applicants, such as in the marriage problem, the amount of time can act as a proxy.

Inspiration For This Article

This book was my inspiration for this article. If you’re interested in the best way to approach any decision in life, I think you’ll like it too.

Writing The Code

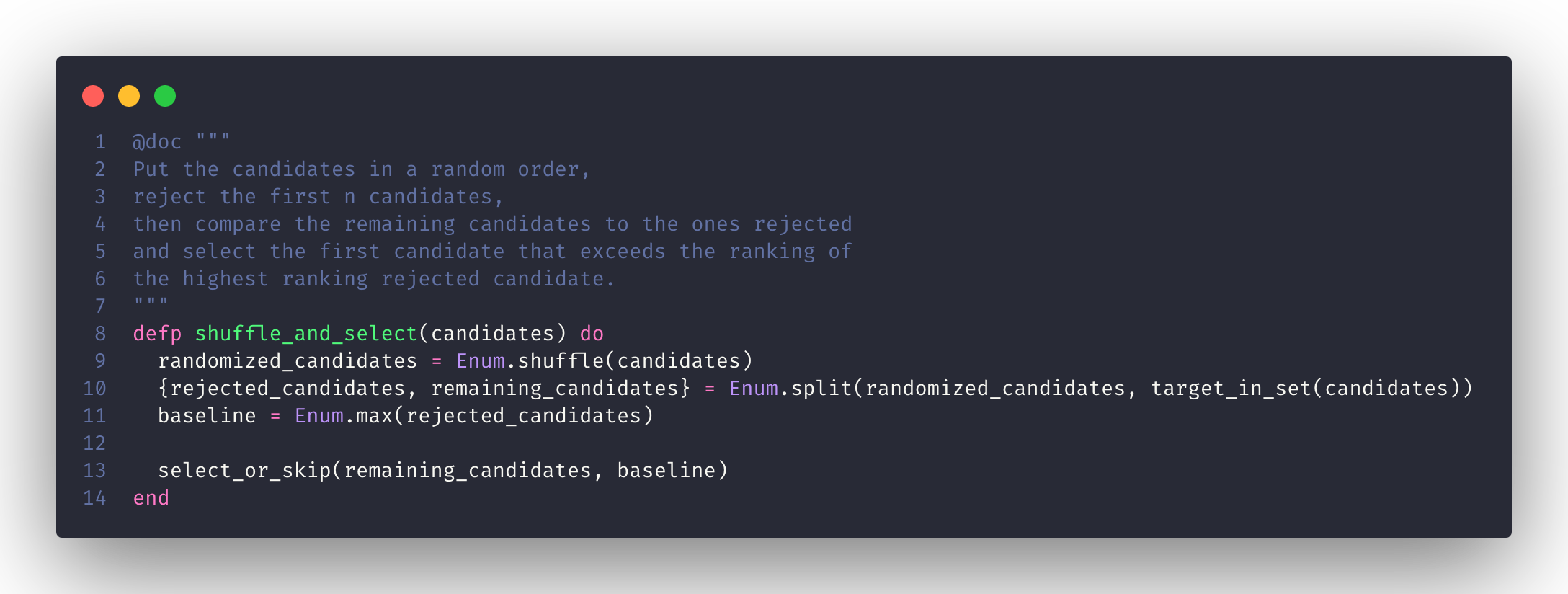

The heart of the Elixir code is the shuffle and select function.

It takes a list of candidates (represented as their qualification score - higher is better.)

First, it randomizes the order of candidates.

Then we get to the interesting part of the solution - the rejections.

Conceptually, when trying to find the best applicant, you are judging them against their competitors.

Given a set of applicants, knowing you must hire exactly one of them, you are not hiring the best secretary in the world, just the best secretary in your applicant pool. This fact remains true no matter what position you are hiring for.

In order to make a judgement, you first need to get some information on the available candidates. You cannot judge an applicants relative ability without information on the applicants you are comparing them against.

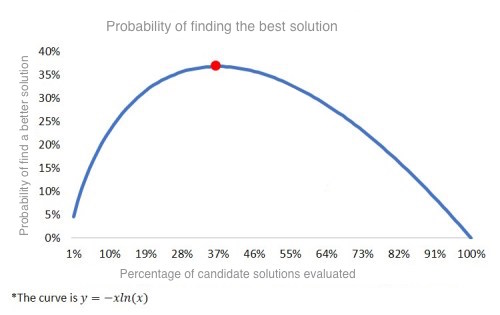

The 1/e law

The 1/e Law takes its name from the asymptotic behaviour of the success probability: the ratio 1/e corresponds precisely to the value at which the success probability P(R*) converges for large N. Here, the letter e denotes the Euler’s number, and indeed 1/e is about 1/2.72≈0.37, as can be seen from the plot.

The 1/e stopping rule applies here. It is named such because it has been determined that using 1/e (or approximately 0.37) yields the best results about 37% of the time, which is the best odds in this scenario.

Using this rule, we go into the interviews knowing we will reject the first 37% of candidates. Now, this seems unfair to the first 37% of candidates, which is why we have to randomize the applicants and also they must not know their place in the order (or not know our 37% rule.)

Back to the code…

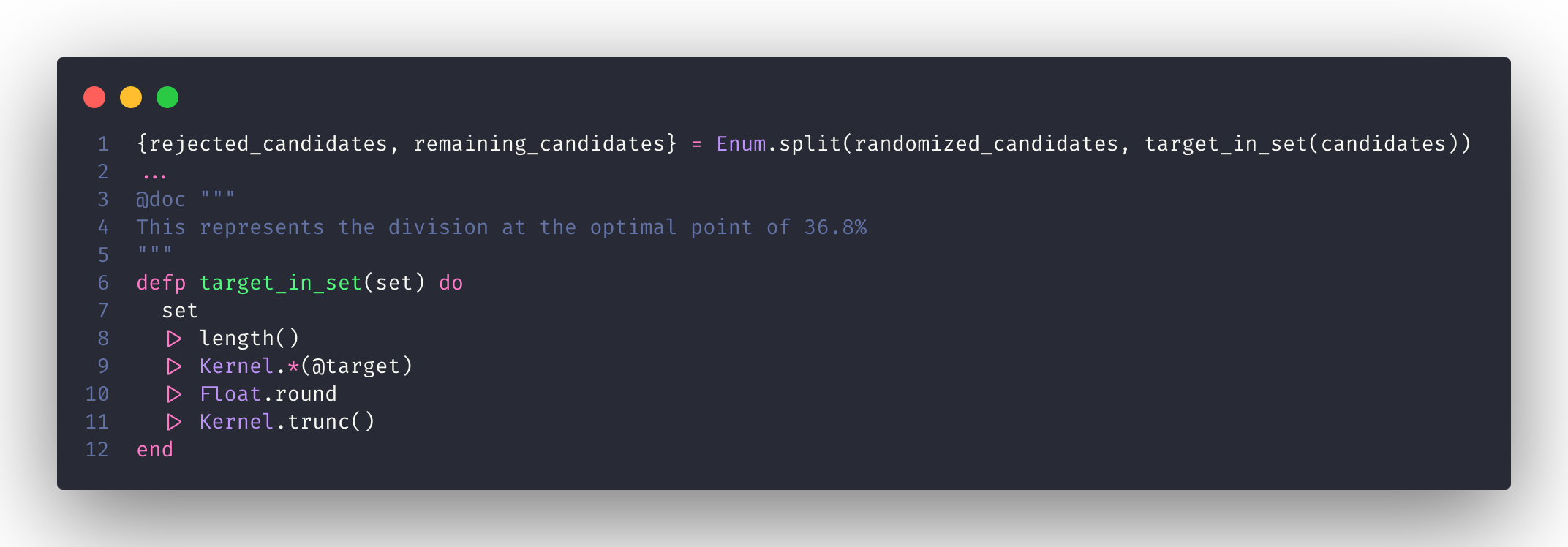

After randomizing the set of applicants we split them up into the rejected list and the remaining list. The target_in_set/1 function finds the place in the list closest to 37% where we split them.

After randomizing the set of applicants we split them up into the rejected list and the remaining list. The target_in_set/1 function finds the place in the list closest to 37% where we split them.

The rejections are not just in vane. We are using them to gather information. Specifically, we want to know how good the best of those rejected candidates is. We are comparing the remaining applicants to that person.

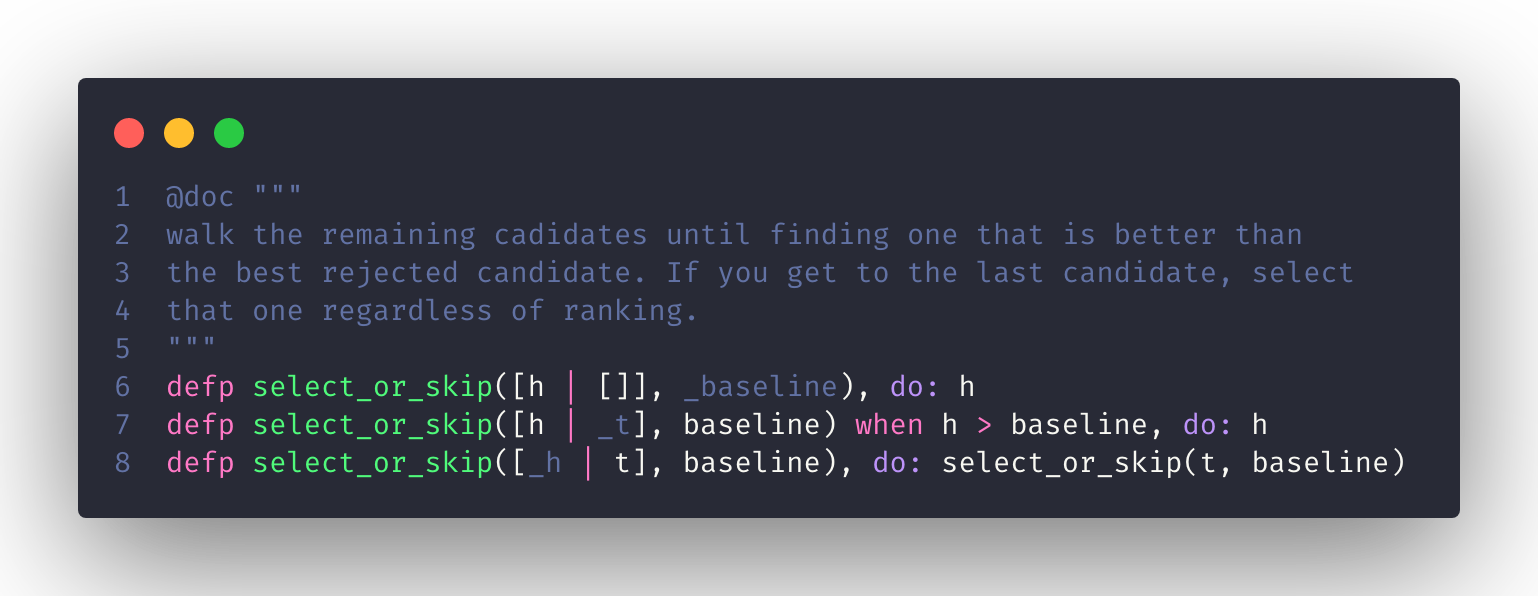

The select_or_skip/2 function is used for that comparison. If you are new to Elixir, this might look odd to you. This is an example of a recursive function.

The select_or_skip/2 function is used for that comparison. If you are new to Elixir, this might look odd to you. This is an example of a recursive function.

The first 2 function heads will stop the recursion. The first function head stops the recursion when we get to the last candidate. No matter how bad that candidate is, we have to hire someone for this job. This actually happens only when the best candidate was in the rejection list.

The second function head is the important one. The logic behind this solution is that you hire the first applicant that exceeds the quality of the highest rejected candidate. This function exits when it finds that applicant.

The last function head performs the recursion. If neither of the above criteria were met, it walks the list.

Testing

As with any theory, it can only be validated by testing.

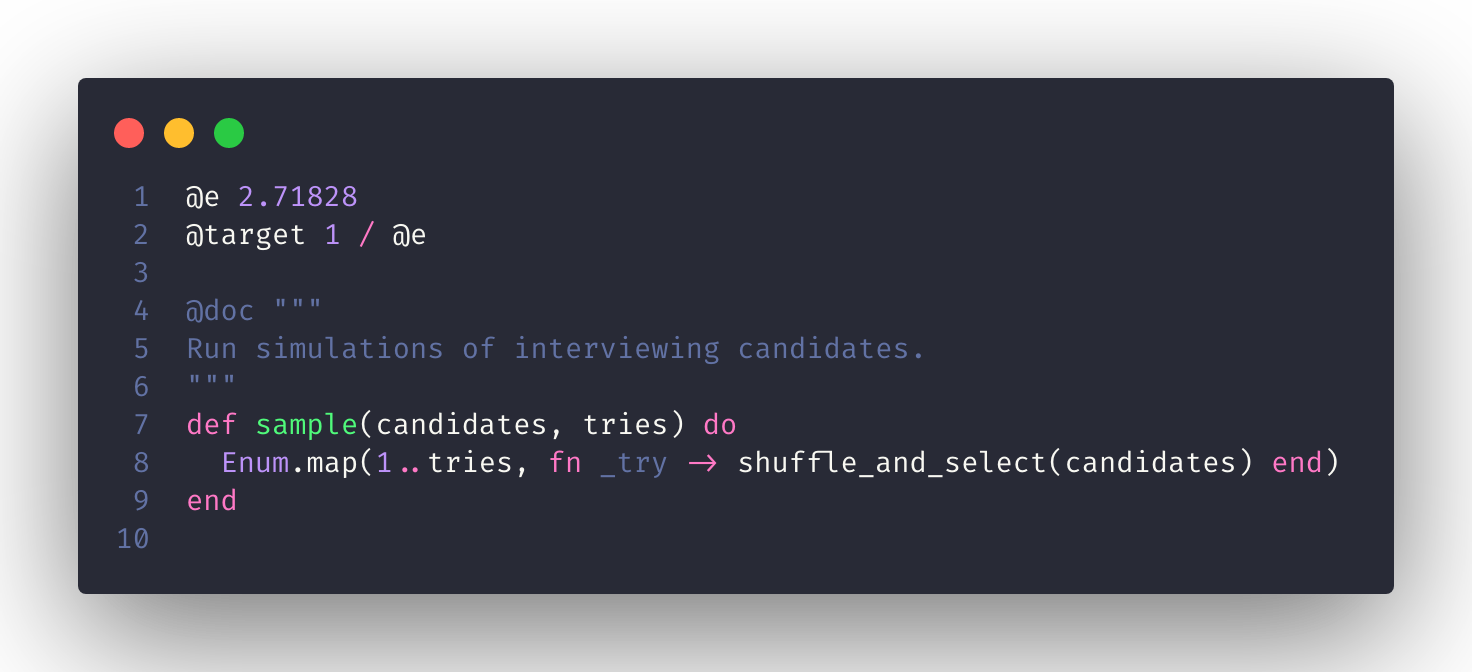

To serve that purpose, I added the sample/2 function. It takes a list of candidates (their quality score to be exact), and the number of samples to run.

This function returns a list of the quality score of the candidate selected in each sample.

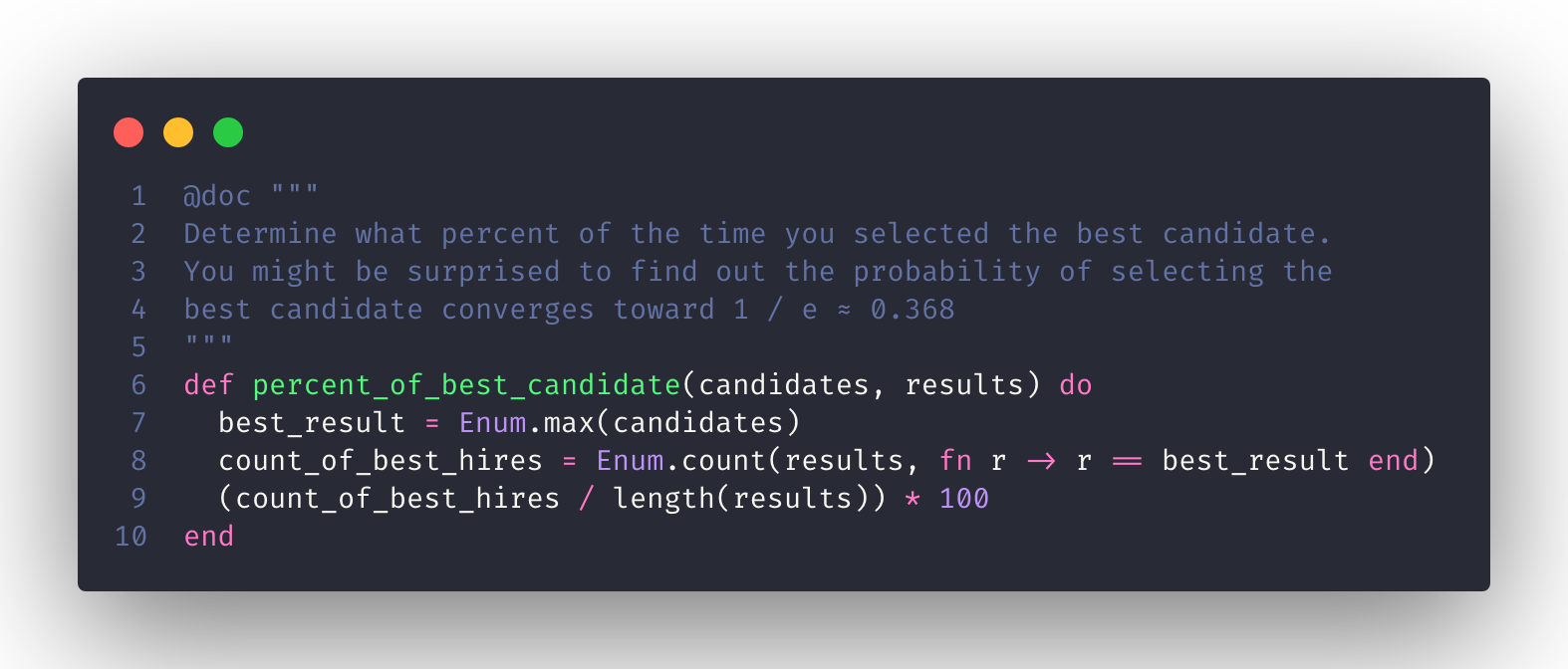

One way to evaluate that is to see how frequently the highest quality candidate was selected. Given the sample size being large enough, we should see a rate around 37%.

The Results

I set up a Livebook to run some tests of the code and to see how it performs.

You can see the results. Notice how they change as the sample size increases. As you approach infinity, that number should get closer to 37.8%.

Conclusion

This was a fun logic problem to learn about and solve using the Elixir standard library. While the idea of hiring a secretary this way seems contrived, I do think this algorithm makes more sense in dating. Given a number of years between when you start dating and when you reach the oldest age you would like to be married, you can apply this same logic. Reject all of the partners you date in the first 37.8% of the time you have given yourself. Then, marry the first partner you meet that exceeds all the other partners you’ve dated.

The code and the livebook are available in this Github repo.